Text: Susie Parr

It is a fine summer day. The loudspeaker gently drones. Wisps of cloud float across the sky while a breeze lifts and lowers the flags around the racecourse. Holding on to their hats- flighty creations in ribbon, chiffon, feathers and flowers- women in dresses of yellow, lilac, lime green, turquoise and cerise pick their way across the turf to the viewing ring. The men are more sombre in suits and ties. Some wear blazers. One sports an elderly panama. They shake hands with each other and murmur: ‘Good to see you old boy. When did you get here?’

Ascot? Epsom? No: Nuwara Eliya, a hill town lying 1889 metres above sea level in the heart of Sri Lanka. It takes around five hours to drive from Colombo, Sri Lanka’s capital city, up to Nuwara Eliya, or ‘Little England’ as it is known on account of its temperate climate and fertile soil. The road from Colombo winds through lush plains, paddy fields, lowland towns and jungle where wild elephants roam. As the road starts to climb, the tangle of growth slowly gives way to mango and avocado plantations, hill villages, forests of spruce and fir and then to the high tea estates, with flat, neat bushes covering every slope as far as the eye can see. The views offer the traveller a fabulous distraction from the many trials of this road: landslides, the interminable road works, vertiginous drops and the hair-raising finale of zig-zag climbs and hairpin bends.

Nuwara Eliya seems a typical Sri Lankan town. Pineapple, jackfruit, mango, avocado and plantain spill from roadside stalls. The pitted, dusty main street is thronged with shoppers: women elegant in saris and salwaar kameez, orange-robed Buddhist monks with umbrellas and briefcases, men walking barefoot, their lunghis topped with anoraks and woolly hats in deference to the high altitude. The call to prayer wails above the racket of pop music, buzzing tuk-tuks and the roar of the mighty TATA lorries and buses that scatter the crowds, horns blaring, then choke them with noxious clouds of black smoke. As the diesel lifts, more complex odours tease the nostrils: spices, fried hoppers, roast peanuts, dried fish, a foetid aroma of hanging meat, the occasional waft of sewage.

Perched on a grassy hummock with a bright red pillar box gleaming by its entrance, Nuwara Eliya’s post office rises impressively above the bustling exoticism of the town. Its clock tower, spires and turrets, cottagey windows and unfeasibly red brickwork and beams make the post office, which was built in 1894, seem as if it would be more at home in a model village on the Isle of Wight. Further down the road, outside Cargill’s Stores, varnished wooden signs list the commodities long ago available within: waterproofs; ladies drapery; sporting goods; gramophones; travelling requisites.

These are relics of the British era in Sri Lanka. Settlers developed Nuwara Eliya as a hill-station in the heart of their tea estates. It became a place where planters, businessmen, diplomats and soldiers could escape the steamy heat of the lowlands and enjoy some home comforts. Here they built elegant villas and bungalows, with white fretwork and green corrugated iron roofs. They grew English flowers and vegetables. They established a golf course, a park, a club, several half-timbered hotels and guest houses and the race-course. Nuwara Eliya became a true home from home. When the British left Ceylon in 1948, these oh so English institutions and traditions, far from slipping into neglect and decay, were taken over, tended and nurtured by the Sri Lankans. In Nuwara Eliya you can find the ex-pat way of life carrying on just as it did in the early part of the last century.

The big hotels (The Grand; St Andrews; The Heritage) are locked in horticultural combat. Sparrows hop across immaculate lawns, where the not a blade of grass bends the wrong way to spoil the mowers’ stripes. Curved herbaceous borders burst with hollyhock, lobelia, cosmos, penstemmon, larkspur, allium, sweet pea and rose. At the St Andrews Hotel, the topiarist’s imagination is unfettered, as a yew whale breaches in a sea of green. These gardens are not just English, they are positively Victorian, created and maintained under the same conditions as the horticultural constructions of the nineteenth century. A plentiful work force of cheap labour (mostly Tamil) tends, weeds, stakes, forces, labels, propagates, clips, prunes and mows, working towards the climax of the horticultural year: the Flower Show, in 2005 opened by the Prime Minister and held in Victoria Park. Established in 1899, the park is fringed with eucalyptus and dotted with specimen trees and shrubs forming the background to more magnificent herbaceous displays. Once the domain of English ladies and gents, here you see Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim and Christian families strolling, posing for photographs by the flowers and playing cricket, Sri Lanka’s national obsession. Notices in the park exhort the strollers to ‘refrain from plucking the blooms’ and to ‘behave decently.’

The golf club thrives. Members work on their handicap then lounge on cane chairs on the verandah with a beer or gin and tonic, looking out over the miniature course, the drives and greens immaculate: tended, raked and swept. Most exclusive of all, The Hill Club is a low granite building redolent of a Scottish baronial hall. It now holds a large Sri Lankan membership and has a lengthy waiting list. Here jacket and tie are obligatory garb for dinner. In the winter a wood fire burns in the lounge and the room boy places a hot water bottle in every bed, to protect residents against the night chill. Such precautions are unnecessary in April, Nuwara Eliya’s summer season. The Hill Club is booked out. Its windows are cast open to the sweet hill air and vases of freshly picked flowers gleam on polished tables. The gravel on the drive crunches beneath the tyres of Mercedes, BMWs and 4 x 4s.

Less elevated guests pile into The Grand, St Andrews, The Glendower and the town’s plentiful guest houses. The road from Columbo becomes clogged with minibuses grinding up the hill, transporting extended families and groups of young men from the pre-monsoon heat and humidity into the cool. Nuwara Eliya lays on all kinds of attractions for its visitors: stalls selling toys, jewellery, fast food and beer; tennis and golf tournaments; the flower show, the horse show and of course the races. Illuminations glimmer from every tree and every bush. Senhalese pop, ads and jingles are relayed at ear-splitting volume from the loudspeakers. Visitors edge round the circuit of roads, bumper to bumper, drinking it all in. Not so much Surrey, more Blackpool, this is Nuwara Eliya’s equivalent of the Golden Mile. There is even a funfair with a Wall of Death, a ferris wheel that looks as if it has been made out of Meccano and a roundabout where each revolution is accompanied, incredibly, by a live band. Gangs of youths, topped up with Lion beer, wander the streets. Dressed in football shirts, cropped trousers, trainers and reversed baseball caps and sporting gold jewellery and mobile phones, some circle the town in customised roadsters, pounding hip hop, looking for any opportunity to put the foot down and add the roar from outsize exhausts to the general din.

And it’s not only exhausts that are big. Sri Lankans are naturally slender but a good proportion of Nuwara Eliya’s visitors come super-size, forgoing fish and vegetable curries and rice in favour of pizza, lasagne and French fries. For those labouring in Nuwara Eliya’s fields, gardens and hotels, it is hard to see the wealthy incomers enjoying attractions that they themselves cannot afford. But the Season brings plentiful work and there is always the possibility of a tip.

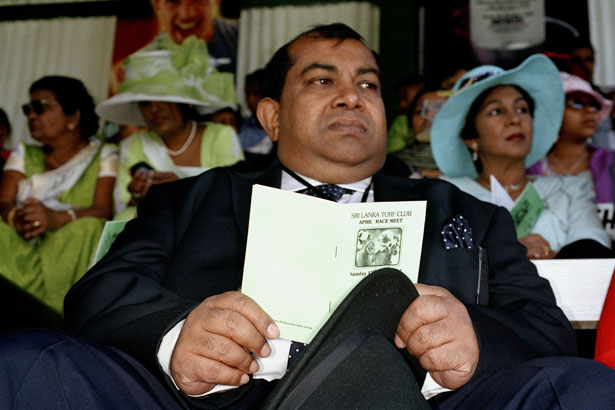

Back at the racecourse, Amazon Bronze has just romped home in the IDC Gold Cup to cheers from the crowd thronging the miniature grandstand. Winnings are hardly massive (the owners pocket only 40,000 rupees, just over £200). It is hard to see how they can afford to maintain this sport, with all the expense of transporting the horses up from Colombo for the occasion. They have no opportunity to race elsewhere in the country: this is Sri Lanka’s only remaining working racecourse. But the crowd is big, the mood is jovial and Sri Lankan Turf Club officials look satisfied with the day’s events, particularly when the Prime Minister arrives to take tea and eat cake in the members’ enclosure.

Although Nuwara Eliya is not anywhere near the area affected by the tsunami, it has felt the impact of dwindling tourist numbers. The Season is regarded as particularly important as the means of reviving the town’s fortunes. The 2005 Season Programme read: ‘Aftermath of tsunami brings a lot of sorrow and pain in mind. Whilst you enjoy the fun and frolic please bear in mind that we have a national duty to bring back the glories of our nation which we have lost by nature, fulfilling our goal to preserve our town as the Little England of the past.’

Back at The Hill Club, things go on as usual. The clock ticks, attendants serve tea and flick dust from the horns and antlers of various wildlife trophies on the walls. The gentle murmur of conversation rises and falls in the reading room. One almost expects Miss Joan Hunter-Dunne to stride in from the tennis courts and order a lime-juice and gin. The England of Betjeman and Wodehouse, along with the sparrows, is safe in Nuwara Eliya.

Comments are closed.