A day at the beach is the same the world over

Text: Susie Parr

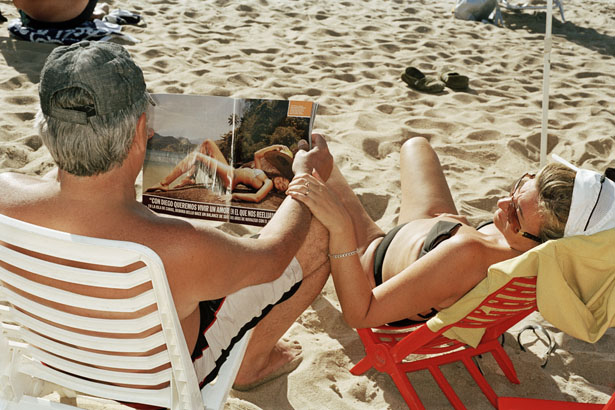

A day at the beach is the same the world over. You find a place to sit, organise your parasol and chairs, then set out refreshments, reading material, towels, bucket and spade. Revealing your beach-wear, you anoint each other with sun cream, take a dip, chat, watch over the kids, flirt, read, eat and drink, enjoy a game of football, listen to the radio, have a snooze and of course closely scrutinise the physiques, outfits and behaviour of your neighbours.

These may seem pretty standard activities, but the style in which they are carried out varies from beach to beach, from country to country. Latin American beach behaviour is so specific and idiosyncratic that an observer can identify the nationality of beach-goers just by looking at where they are sitting, and with whom, what they wear and consume.

Take, for example, the mix of different social groups that occurs on most beaches. On Copacabana, you can tell you are in Brazil simply by the sheer variety of people rubbing shoulders on the sand: the country’s diverse population in microcosm. Black and white, old and young, rich and poor: all mingle on the same expanse of sand and stare at the surging green surf. Stunned by this free for all, newly arrived tourists sweat pastily in the steamy heat, blinking in the startling light and tasting the salt spray on their lips. Then they strike out for out the safety of their hotel encampment on the sand. Here, sunbeds, parasols and fluffy towels recreate the order – if not the cool – of the hotel room and offer relative protection against youths on the prowl for unguarded possessions and the relentless attentions of the vendors. With the diversity of Brazil comes a certain edginess that is perhaps less evident on the more sedate, homogenous beaches of Chile, Argentina, Mexico and Uruguay.

Not every beach in Brazil offers such a mix. You can glimpse the enclaves of the privileged as you slog up the hill from Salvador’s Barra beach under the scrutiny of security guards, past electric gates that protect the private dwellings and well tended gardens of the rich. Down below, all is calm: a smooth ash deck, an elegant expanse of white sand, pristine parasols and sunbeds, waiters bearing drinks, jet skis bobbing in the azure water. In complete contrast, Ribeira beach is mainly populated by working class and poor Salvadorians. Every inch of sand lying in the curve of rock is packed higgledy piggledy with tattered sombrillas and grubby, rickety plastic chairs. Axe and pagode blast out from the café speakers. Family groups dance, chat and cool off. Ragged children, hoping to pick up a few reals, tote plastic trays of fish fried in red palm oil and garnished with lime, from table to table.

I watched a family arrive at a Ribeira beach cafe with two little girls, one about five years old and the other, a baby of perhaps six months, with curly black hair pulled into a topknot, pierced ears and a bracelet on her chubby wrist. Their mother removed the baby’s dress and nappy and then on went a miniature orange bikini and a pair of tiny sunglasses. The older sister (already kitted out in blue bikini) sucked her thumb and swayed and wriggled to the rhythm of the music. The girls were all set for a lifetime of days at the beach. Their elderly grandmother looked on smiling. Behind her, across the bay, I could see palm trees and the ruins of a colonial building. I wondered if her own grandmother might have been one of the many millions of slaves imported from Africa to work on Brazil’s sugar plantations, many of whom were processed in Salvador.

The other characteristically Brazilian feature of beach life is the relaxed approach to the human body. Fat, thin, old, young, smooth, wrinkled, beautiful, ugly- no-one minds what you look like. Little is left to the imagination. The famous ‘dental floss’ bikini bottom adorns backsides of every imaginable size and shape, not just the peachy perfection of the many beautiful caporicas who frolic on Copacabana’s sand. At the end of a long, hot day, I watched an elderly beach vendor of ample proportions slowly trundling her cart of wares towards a beat up VW campervan waiting on the other side of the road. Wearing a miniscule macramé bikini with nothing but a string between her buttocks, she tramped across in front of six lanes of waiting traffic without any sign of self-consciousness. The Brazilian ‘anything goes’ approach to the body soon rubs off. Even the shell shocked Europeans start to relax, confidently exposing their wintery flesh to the sun’s rays.

My English fifties-style costume, all gussets and panels, would run to about forty sets of Brazilian swimwear. It is more in tune with the beachwear in Chile’s Vinha del Mar where elderly women sit under parasols wearing sunhats, blouses, skirts and pop-socks, or stand at the water’s edge, clad in swimsuits with underwired bosoms and generous skirting. As the Pacific laps at their ankles, they cautiously watch over the little ones, supplementing the lifeguards’ gaze. Squadrons of pelicans patrol overhead and in the distance, tankers move slowly towards Valparaiso. Mexican beach-goers seem even more modest, often covering up with tee-shirts and shorts as they loll in the water. In Mar del Plata, Argentina’s largest resort, the upholstered look is de moda for the many older people who retire there or migrate in every summer. The silvery expanse of sand is a soft blur of activity as mature holidaymakers stroll along the shoreline, paddle, wade or wallow in the warm shallows, gazing out to sea and chatting with friends. In sedate Vina del Mar, thanks to the icy Humboldt Current that runs all the way up the Chilean coast, there is little evidence of lounging in the Mexican or Argentinian style. Here, bathing is a Spartan experience, and most people content themselves with standing at the water’s edge or perhaps jumping the waves.

Mar del Plata’s beach is similar in size to Copacabana but the atmosphere couldn’t be more different. Instead of fearsome, swirling, dazzling green surf with its spin and tumble of shrieking urchins, the flat water glistens dully. Slowly, it creeps up the grey sand then recedes, leaving behind a sluggish scum of rubbish (cigarette butts, straws, tissues, orange peel, bottle tops). I watched one holidaymaker neatly scoop the detritus aside with a flip flop in order to clear his chosen patch of sand. Instead of the spontaneous and stunning displays by acrobatic, somersaulting beach footballers that crop up all over the place on Copacabana, football pitches are marked out at a particular level on the damp sand. That’s where football is played, not anywhere else.

Every inch of the beach at Mar del Plata is at a premium: space is contested and ordered. At the very top of the sand-line, at the foot of the looming hotels, tight rows of ‘balnearios’ or bathing stations offer privacy, shade, sunbeds and refreshments to those who are willing to pay. From here, ropes stretch down marking out protected walkways towards the sea. In front of the balnearios, symmetrical rows of sombrillas and chairs are available for hire. In front of these, members of the public can stake out their own patch with parasols, folding chairs, towels, mats and cool boxes. And finally, the games area reaches nearly to the water’s edge. In this patch of sand, you will find the young busy with their excavations: industrious, concentrated and serious.

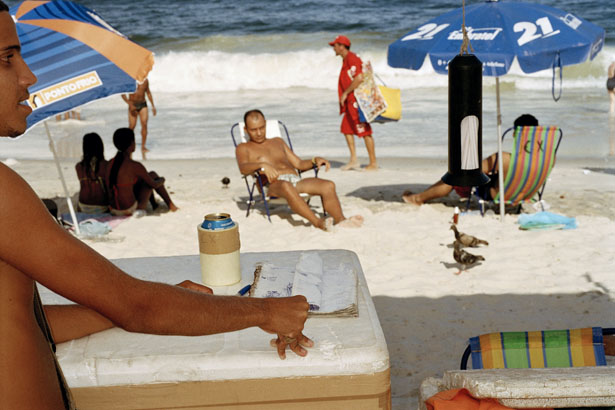

Unlike Mar del Plata and Vinha del Mar, where beach activities are compressed into regulated areas, the expanse of sand at Copacabana is so vast that any orderliness is perhaps more temporal than spatial. Walkers and joggers -all lurex, pedometers and ipods – appear at the water’s edge early in the morning before the heat of the day has a chance to build up. Meanwhile, beach vendors arrive with their carts and start setting up their pitches. Then the tourists emerge bleary-eyed, basting themselves with oil and slumping on sunbeds to gently cook away the night before. Although Rio’s street children, who seem to have no fear and certainly have no-one looking out for them, spin around in the surf like flotsam, only the strongest and bravest tourists dare struggle through the wall of foam and the vicious undertow into deep water. Most in search of cool have to make do with a paddle or a cerveja.

Then Copacabana’s interminable procession of beach vendors starts up, trailing from chair to chair as pigeons coo and court on the burning sand. Vast tankers move slowly across the horizon, making for Santos, silhouetted against the cumulus clouds that build up slowly in the heat. In late afternoon, when school is out, football training and matches of no-hand volleyball start up on the many courts and pitches set along by the road. Then as the sun goes down and vendors begin to pack up, more joggers and walkers emerge. In the relative cool, panting poodles wearing frilly sundresses are walked by minders past flea-ridden mutts slumped under a café table or a palm tree. And as it gets dark, you can make out the shadowy shapes of the poor bedding down on the sand, away from the street lights. On Santos beach, whose attractions entice thousands of Sao Paulo residents to drive the 57 kilometres across a mountain pass every weekend, arc lights have been fixed up so that the partying, barbecuing and football can carry on in the hours of darkness.

Every beach has its diurnal and nocturnal rhythms, rituals and routines, some public and some private. Sitting in a scrap of shade at the scruffy end of Punta del Este, the pride of Uruguay, far away from the swish restaurants, cocktail bars and jewellery shops, I realised I was encroaching on the territory of an elderly couple. They arrived at 11 am with their fold up chairs and picnic and sat, alternately reading their papers and gazing out to sea. Looking up at the road that winds gently up the hill, I saw another older woman wearing a sunhat, also carrying a fold up chair and bag, walking slowly down towards the beach, followed at some distance by a panting, grizzled dog with arthritic paws. Eventually, they too reached our patch of shade. The woman greeted the couple, and sat down next to them, while the dog slumped on the sand and fell asleep. There was some chatter and an exchange of biscuits. After a while the new arrival stood up and slipped off her sun-dress to reveal a bathing suit, and walked towards the sea. Seeing this, the dog sighed, struggled to his feet and padded off in her wake. She entered the sea and swam slowly back and forth in the shallows for about twenty minutes, while the dog stood with his paws in the water, wagging his tail and watching her. Then back they came and she sat and dried off, before slipping her dress back on and walking up the hill, followed by the dog. Home for lunch and perhaps a nap. I watched this happen on two consecutive days and imagine that the gentle ritual had been going on for years and would continue for as long as both could manage it.

Punta del Este, with its white sand and clear blue sea, is the summer playground of well-off Uruguayans. But it also lures rich Argentinians away from the claustrophobic summer heat of nearby Buenos Aires, a city that feels landlocked despite being coastal. Portenos either board the giant catamaran that swiftly covers the distance back and forth to Montevideo, or fly from Aeroparque Jorge Newbery, Buenos Aires’ domestic airport, whose runway lies parallel to the estuary. Here, Argentinian fisherman stand for hours casting their lines into murky brown water, scarcely glancing up at the elderly Aerolineas Argentinas planes as they shudder into the clouds overhead.

In Punta del Este, as everywhere, beach-goers quickly become sitting ducks. Every Latin American beach seems to have the same endless supply of patient, hard-working vendors. Throughout each long, hot day, they trudge up and down, calling out their wares, watching intently for any flicker of interest that might signal a potential sale. Of all Latin American countries, perhaps Mexico provides its beach-goers the most extensive range of retail opportunities. The frequency with which food, drink, clothes and novelties are offered makes it impossible to concentrate on one’s reading for more than two or three minutes at a time. Sitting on Acapulco’s town beach and forced to give up on my book as wave after wave of hopeful dealers approached my chair, I decided to note down every item I was offered within the space of one hour:

Pistachios; doughnuts; a head massage; individual puddings and jellies carried in a glass case; mango, watermelon or orange on a stick; nachos; bracelets; hammocks; statues; sarongs; sunhats; flip flops; wooden jugs; Coca Cola; tarot cards; bags of shrimps; ceramic dolphins; blankets; life jackets; bananas fried in syrup; trays of oysters served with a twist of lime; apricots; sunglasses; water; freshly caught swordfish; a blood pressure check; newspapers; bubbles; peanuts; kites; glass mobiles; guacamole; swimsuits; shoes; enchiladas; wooden parrots; necklaces; gazpacho; refried beans; crucifixes and a serenade by a troupe of mariachis.

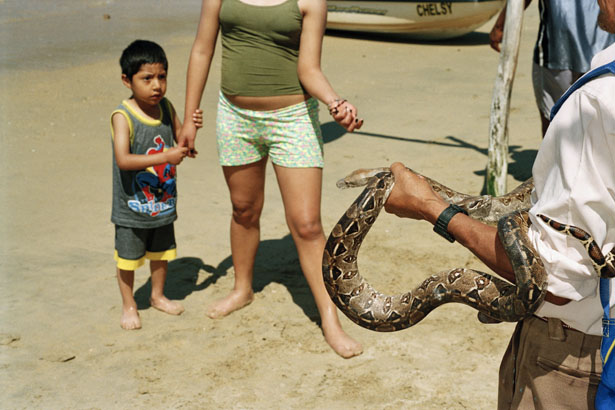

In Acapulco, even taking to the water doesn’t stop you being a potential customer: vendors gently steer their canoes between bathers, trying to draw attention to the shell ornaments displayed on the bow. If you don’t fancy any of the items that are brought to you, you can always stroll to the boat, moored at the water’s edge and fitted with a parasol, where fishermen shuck oysters and display live lobster and crab ready for the pot. This seems somewhat tame compared with the beach wares on offer in Puerte de Marquez, a few kilometres down the coast from Acapulco. Here, as well as buying more regular items like soup and buckets of prawns, you can have your photograph taken with an enormous, writhing snake and take your pick of live turtles and tortoises, although it is not clear whether the latter are sold as pets or food. And beach food is another indicator of nationality. On Santos beach, where on summer weekends the crowds from Sao Paulo are so huge that you can hardly see the water for people, you are offered delicacies like sliced fried coconut, shrimp paulista, sweet corn, and brigadeiros- small chocolate cakes. On Ribeira beach, trays of upturned crabs, claws waving, are toted around awaiting death by barbecue. You can buy cubes of bean curd from a plastic box balanced on the vendor’s head or a small cup of thick, strong, sweet coffee, poured from a grubby thermos flask.

While most Latin American beach-goers consume coffee, beer, water and Coke, the most popular beverage for Argentinans and Uruguayans is yerba mate, a tea made from the leaves of a species of holly. The infusion, which is mildly stimulant, is prepared by repeatedly steeping the dry leaves of the plant in hot water – boiling water makes it bitter. Once infused, it is sipped from a hollow gourd, shared between friends and family, using a metal straw or bombilla. In Argentina and Uruguay, no family group encamped on the sand would be seen without sets of elaborate mate-making equipment comprising gourds, bombillas and flasks of hot water in a carrying case. The wherewithal to make mate is as essential to a good day at the beach as the cool-box stuffed with food.

The beach is the place where public and private worlds intersect, a curious mix of defence and intimacy. Here, unstructured space is staked out and temporarily transformed, through artefact and ritual, into personal territory. In close proximity to others doing the same thing, a bit like being on a long haul flight, people let down their guard, revealing the secrets of their bodies, habits and relationships to anyone who cares or dares to look, as they dream and doze on the sand.

Comments are closed.